Preventing Canadians from participating in the digital economy, especially those in rural and remote locations, “exacerbates the challenges they already face,” according to the report “Broadband Connectivity in Rural Canada: Overcoming the Digital Divide” by the Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology.

“There remain gaps in digital literacy competencies and digital access across the country,” Nisa Malli a senior policy analyst for the Brookfield Institute at Ryerson University says.

Malli, along with Annalise Huynh, wrote Levelling Up, a report that assesses the state of Canada’s digital literacy, which they define as the ability to use technical tools to solve problems.

Levelling Up found that, “Infrastructure gaps in rural, remote, and Indigenous communities, along with financial access barriers among low-income people living in Canada across the country, are contributing to this challenge.” According to the study, these factors further marginalize those who are already face challenges.

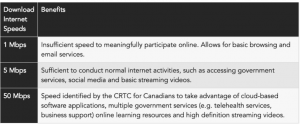

Research shows that gaps are particularly prominent between urban and rural communities. According to Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA)’s Internet Factbook 2018, rural communities have an average download speed of 11.15 Mbps and upload speeds of 5.45 Mbps compared to urban communities with download speeds of 22.92 Mbps and upload speeds of 12.4 Mbps.

CIRA, which is a not-for-profit member-based organization that focuses on developing and implementing internet-based policies, found that “rural communities are about 25% slower than urban ones.

However, it is noted that, “CIRA’s test relies on a crowd-funded model. Rural homes that don’t have internet access obviously cannot run an online Internet performance test.” The fact that most surveys documenting the state of internet access for Canadians are done online is a common problem when collecting data on rural and remote communities.

Colette Brin, a professor of information and communication at Laval University, conducted a study assessing news users as part of the Digital News Report Canada (2016-2018). But she recognizes a challenge in the research process. According to Brin, about 10 percent of Canada’s population is without regular internet access. These people, she confirms, were not consulted in her survey.

To discuss populations without internet, Brin says we would have to go outside of her study. “That’s actually a blind spot of the study because we do only talk to people who are online,” she says, adding that in order to get this information it would require a very qualitative, ethnographic, long-term approach. “Which a lot of scholars are just not trained to do or it’s not something necessarily rewarded also in the academic world we are pressured to produce, produce, produce and publish, publish.”

The 2016 CIRA study found that 13 percent of households across Canada do not have internet access altogether.

“There are significant gaps in broadband access, in terms of basic access and speed,” Malli says. This reality deepens Canada’s digital divide.